Working on prisoner support is one of the most exhausting, transformative, frustrating, vital, tedious, rewarding, messy, wonderful things I have ever done.

When someone is in prison, every moment is a crisis. Even when a specific problem or situation is resolved, there remains an overwhelming survival mentality, which affects those inside and their supporters alike. I move from crisis to crisis every day; meanwhile the prisoners I am not actively engaged in supporting at any given minute hover in my peripheral vision, imploring they not be forgotten. None are ever forgotten, of course, but the need to prioritize presents me with difficult decisions about how to use my time and resources daily.

In the past few weeks, most of my efforts have been dedicated to helping Mark Neiweem, also known as Migs, of the NATO 5. Quick refresher: five activists were arrested days before the NATO summit in Chicago last year and subsequently charged with terrorism. Three remain incarcerated at Cook County Jail, awaiting trial. One accepted a non-cooperating plea agreement and served a sentence of four months in a boot camp for non-violent offenders. He was recently repatriated to his native Poland. The fifth is Mark, who also accepted a non-cooperating plea and is serving two concurrent three-year sentences. With credit for time served and time off for good behavior, he expects parole in November. You can read his comments on his decision to change his plea and his grim experience at Cook County Jail here.

Mark entered his new plea in April. He was immediately transferred to Stateville, where he stayed for one month under barely tolerable living conditions. He was then moved to the medium security unit at Pontiac Correctional Center in Pontiac, IL. This was by far his best housing situation, although it feels strange to put it that way. Prison is always a miserable experience, but there are relative levels to misery.

I got my first letter from Mark when he was still at Cook County Jail exactly one year ago today – the same day I attempted to visit him for the first time. His tone was friendly, engaging, and funny, but he also came across as angry, frustrated, and obviously in pain. In one line that still haunts me, he suggested that they should execute him and let the other four guys walk. When we tried to see him that day, we discovered he had just been hospitalized after being severely beaten by guards. His hospitalization was followed by five weeks in solitary confinement, where he stayed without visits until after his visible wounds healed.

During those five weeks, I made it my personal mission to make sure he always had mail and someone he could call. I wrote and told him that five guys went in, and I would not rest until all five walked out. Ever since, it has been my utmost priority to make sure the shadowy powers-that-be know we are paying attention to what happens to him. As the good Doctor would say, he is protected.

As it happens, we’ve also become good friends. I very much look forward to the day when I can spend time with him that’s not regulated by the Illinois Department of Corrections.

After his conviction and move to Pontiac, I noticed a significant positive shift in Mark’s attitude. I attribute this change to the resolution of his case, having a release date in sight, and having escaped the hellhole that is Cook County Jail. His medium security designation meant he merited “contact visits” where he was able to hug his mom and some friends, myself included, for the first time in over a year. He began making concrete plans for the future and became determined to use his remaining time to educate himself in preparation for release. He requested books, signed up for the prison’s GED class, and began attending Narcotics Anonymous meetings. He mentioned in his letters that some of the prisoners knew why he was there and tried to engage him in conversation about it, but that he had no interest in discussing the past. His sights were set on the front door and he was doing everything possible to get a strong new start on his life.

Imagine my concern and disappointment, then, when I drove down with a friend to visit him in July and discovered that he had been moved to solitary confinement in the maximum security unit. We were still able to see him, thankfully, but it was a no-contact visit. We spoke to him through a sheet of plexiglass and watched as he twisted around, trying to find a comfortable position to sit with his arms shackled behind his back to the base of his stool. He told us he had not been able to contact anyone about his transfer to solitary because he was no longer allowed to use the phone and his property had been seized, which meant he did not have his list of mailing addresses. At that time he had not been charged with any misconduct but was “under investigation,” which meant they could hold him in solitary for at least 30 days.

Despite the circumstances, it was a great visit. He looked healthier and stronger than ever, if a bit scruffy from lack of access to shaves and haircuts. He was funny and thoughtful as usual and clearly determined not to give in to these heavy-handed tactics. He expressed concern over not completing his GED class and the setback in his plans to prepare for release. It wasn’t the most relaxed or pleasant visit, but definitely one of the more important ones.

Cue an endless number of urgent phone calls. We stood in the prison parking lot, phones poised, reaching out to lawyers, his family, and other activists as a thunderstorm brewed in the distance. It was very dramatic, or maybe that was the adrenaline speaking. During the 100-mile drive home, we held an early strategizing session. After the lawyers made their official requests, we launched a call-in campaign, flooding IDOC Director Godinez and Governor Quinn’s offices with demands for accountability. They responded by moving him to a smaller, more restrictive cell within solitary, behind a solid steel door. At one point I found myself sitting on the dirty sidewalk outside CPD District 001 at midnight, waiting for anti-ALEC protesters to be released, typing up actions and campaigns to at least get Mark some mail and pictures, at his request. It’s a glamorous life.

Ultimately, Mark was charged on two counts – possessing “unauthorized” anarchist symbols and possessing “unauthorized” anarchist literature, both of which were deemed an imminent threat to the facility. We are still awaiting a decision on these charges. Assuming they are upheld, he could be moved farther downstate, away from his support system, or lose his time off for good behavior. Or both.

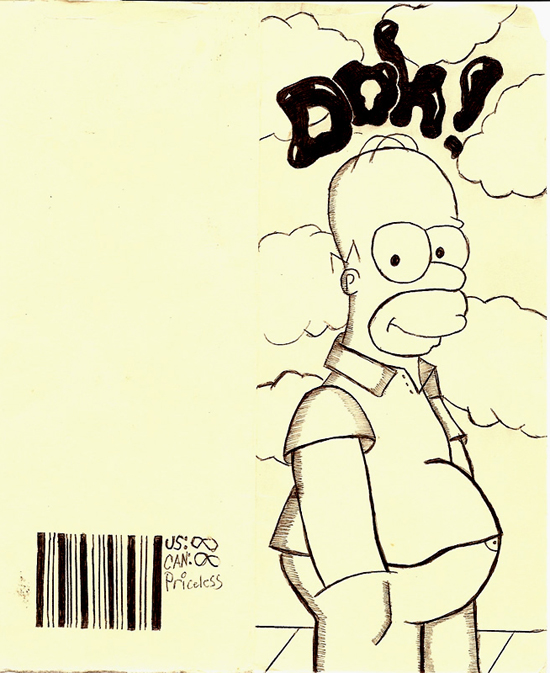

Meanwhile, every moment is a crisis. I walk around with the awareness that his fate is balanced precariously, and there is only so much I can do to help. I send him photos taken in shaded parks along Lake Michigan, where I like to sit and write. He sends me funny drawings to let me know how much he appreciates my support.

This week, I went to visit him again.

I drove down in a borrowed car, pumping donated funds into the gas tank. I brought three books for him:

• On Writing by Stephen King because I am gently encouraging him to write about his experience;

• Packing for Mars by Mary Roach because it’s funny and informative and deals with confinement in small spaces as a means of exploring the vast depths of inner and outer space;

• and City of Thieves by David Benioff because if I sent him on a life-or-death mission to find a dozen eggs in war-torn Russia, I know he would deliver.

I was braced for trouble getting in to see him but it all went smoothly at the gate. In the waiting room I met a woman from the southwest suburbs of Chicago, there to see her brother. We traded war stories about visiting different facilities, always carefully avoiding the question of why we had to in the first place. Prison etiquette.

Finally, I was called to see Mark. He was behind plexiglass again, arms shackled behind his back again. You wouldn’t know it from the grin on his face, though. He looked too skinny and he still hadn’t gotten to cut his hair or shave, so he was starting to resemble the caveman drawings of himself that often adorn his letters to me. It was great to see him, no matter what.

We got business out of the way. He had a productive legal visit the week before. He still didn’t know his fate, but told me he is committed to resisting whatever they have in store for him. He said he was not interested in passively accepting their aggressive tactics, especially since he doesn’t believe acquiescence will result in better treatment. He has clarity of purpose about both his own situation and how it fits into the larger context of the system that keeps him unwavering in his resolve. As his mom told me on the phone recently, “They’re trying to break him, but they won’t. He’s a tough nut to crack.” He still spoke of his plans for the future, but they were more abstract.

He asked about other defendants’ well-being and for general news updates. I felt bad; it seemed like most of what I had to share was bad news. I told him about a contested space in Chicago that had been used as a community center for the past three years – until it was destroyed overnight with no warning. His response? “That sounds like a prime spot to occupy.” I shook my head and told him there was nothing left to occupy anymore; it’s just a pile of rubble now. He smiled. “So, it’s a pile of rubble now. Turn it into an organic garden.”

That wasn’t the response I expected, but it was the response I needed. I am constantly fighting burnout and every pile of rubble looks like a loss, highlighting the futility of our efforts to create sustainable change. He found the hope and possibility for a new beginning that was buried in this one. I didn’t tell him at the time, but hopefully he will read this and recognize that he could not have suggested that a year ago. He’s come a very long way.

I told him about the Netflix show Orange Is The New Black, and how people keep telling me I should really watch it because of my involvement in prisoner support work. I have been watching it, and see both its merits and its flaws, but it is slow going. I spend so much of my day worrying about prisoners and their perpetual moments of crisis that it is hard to sit back in my downtime and watch a TV show about it. Even harder to laugh. He compared people telling me to watch the show to prisoners who never miss an episode of Cops, or love detective shows that glorify the police force, without a deeper understanding of how it compounds their own oppression.

He wants to teach people about how the state uses incarceration to drain our power and resources and ability to resist. He wants every activist to know about the prison industrial complex, not just in theory or from a TV show, but from experiencing it alongside somebody trapped in the system. At least until they are all free.

He also expressed an interest in environmental activism as his next endeavor. When I mentioned some of the ongoing struggles against the KXL pipeline and fracking, he looked sad. “I’m missing so much in here,” he explained. I promised him we wouldn’t fix the whole world without him, but would leave something for him to work on when he got out. He’s holding us to that promise.

(This part of the conversation reminded me of my visit to Brian Church, also of the NATO 5, two days earlier. Brian was trained as an EMT but will never be able to work in that field again due to these charges. He very much wants to volunteer as a street medic to help people rising up against dictatorships in other countries – if he can work out a way to travel – who often end up badly injured. His desire to use his own skills to help other people was palpable, even with his own fate still undecided.)

At one point, Mark went off into an earnest and passionate political discourse, talking about how ridiculous he finds the concept of asking elected officials to honor rights we already have. If they really represented us, he theorized, we wouldn’t have to ask them to be on our side and protect our innate freedoms. “You can’t ask for permission to be free,” he told me. “You just have to start being free.” He interrupted himself with a sheepish smile. “I’ve been reading a lot,” he apologized. I looked at him, wearing “more chains than the Ghost of Christmas Past” (as he once described it to me), and I knew that he was free. They have imprisoned his body but his soul is soaring above it all, and he will prevail.

Every moment of prisoner support work is a crisis. But here’s the secret I saved til the end: every moment is also a precious gift. I have friends I haven’t talked to in months because I’m secure in the knowledge that I can text them at any time. My time interacting directly with prisoners, however, is measured and cut into segments that are never quite large enough. We don’t waste our moments together. Each and every one is important.

Before I had to leave, I asked Mark if we could do anything more for him right now. He is getting his mail again, very slowly, presumably after being read and documented by the prison. It is his only link to the outside world, and he asked people to continue writing and sending him photos. You can learn more about how to do that here.

When I hit the halfway point on my way back to Chicago, I suddenly started crying. I didn’t want to leave him behind, but I had reached the point of no return and had to keep pushing forward. I remembered a final bit of wisdom he had left me with: “It may feel like you’re on the ropes a lot, but at least you’re still in the fight.”

When every moment is a crisis, every moment is also an opportunity to resist and push forward. This is my work and my calling, but you can be a part of it to whatever extent you are comfortable. Choose one person on the #OpPenPal mailing list and send them a letter or postcard that will make them smile. If you live in the area of one of these cases, reach out and ask what court support and jail visit needs are, and if you can tag along with a veteran your first time. Donations to defense funds are always appreciated, and if all else fails, sharing links and information with your family and friends helps get the word out.

“Solidarity is our best weapon, and it works.” – Mark Neiweem, Open Communiqué

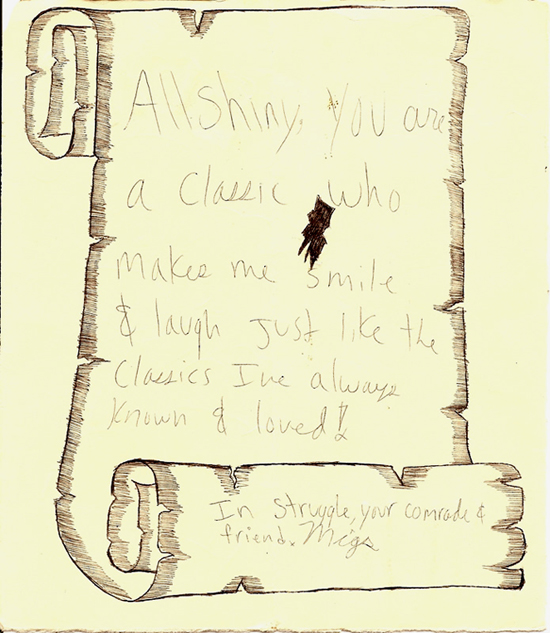

Rachel Allshiny served as librarian and press liaison for Occupy Chicago and co-founded OpPenPal in February 2013.

Related Posts:

Love In A Time Of Mass Incarceration