by Brett Warner

Few bands manage to perpetually frustrate their fans the way Weezer does. With each new album, singer/songwriter Rivers Cuomo – a semi-secret musical genius, we’ve been instructed to keep in mind – continues to disappoint a very vocal legion of cynical, skeptical, and especially jaded twenty-to-thirty somethings with one word on their tongues: Pinkerton. No other album in rock history (save maybe Sgt. Pepper) gets tossed around as much; you won’t find any Weezer album review after 2001 that fails to mention it. The 1996 proto-emo classic was a commercial flop upon its release, but word of mouth and the band’s 5-year hiatus lifted it to cult classic status. Its supporters tend to hail the album’s intensely personal lyrics: a smorgasbord of frustrations aimed at groupies, lesbians, Asian girls, and Cuomo’s various other insecurities. Weezer’s latest album Hurley (their first on independent label Epitaph Records) has gotten some choice positive reviews, many comparing its rougher, lo-fi sound to Pinkerton’s – but still, many rock fans seem unwilling (or unable) to give the band another chance. To them, the deeply confessional tone of Pinkerton’s songs has been replaced on post-millennial Weezer records with sarcastic, ironic, sophomoric humor – when in actuality, Weezer have never been ironic. They are quite possibly the only completely honest, agenda-less band to come out of the ’90s alternative boom. So why the shift in general cultural opinion of the group? The reason why Weezer continues to frustrate listeners is because they draw attention to the generational shift between X and Y listeners. Throughout this significant transition in social attitudes, Weezer have remained remarkably consistent – we’re the ones who’ve changed.

In his latest book Eating the Dinosaur, pop journalist Chuck Klosterman discusses this schism between Weezer’s very face value brand of rock music and a generation of kids raised on double-meanings and cultural facades:

“If every new record a certain band makes disappoints its base, one would assume chagrined consumers would eventually give up. But people have a different kind of relationship with Weezer, and it’s due to the songwriting of front man Rivers Cuomo: He writes completely straightforward lyrics, presented through music devoid of irony. He exclusively presents literal depictions of how he views the world…Audiences are unwilling to view Weezer’s music as a reflection of Cuomo’s autobiography. They think it must be about something else; they think it must have something to do with them, and with their experiences, and with what they want from pop music. They are disappointed that Weezer’s post-Pinkerton music doesn’t sound honest…But the reason it sounds that way is because it’s only honest. It’s so personal and specific that other people cannot relate to it. And – somehow – that’s assumed to be Cuomo’s job.” (page 227, 228)”

Klosterman proposes that Pinkerton connected with listeners purely by accident; that an album so nakedly honest and personal could only be digested (in 1996) as a sort of metaphoric construct, designed for each individual listener to personalize and inhabit as their own. If anything, Weezer’s music has grown more personal and specific, to the point of alienating those who would aim Cuomo’s lyrics towards their own experiences. Like the young people that still buy their music, Weezer express themselves in an increasingly literal manner. The Gen-X art of mixtape making has been replaced by the iTunes Genius – Kurt Cobain’s diary has become Kanye West’s Twitter. Kids raised on the internet and social media view the world in a much more open, less private way than their parents or older siblings. The entire notion of a social media community – complete with stats, Likes, and moment by moment status updates – negates the imperative for artistic self expression. Why write “Across the Sea” when you can just blog about it? Rivers Cuomo’s songs have always utilized this open book approach, and as the culture began to move in that direction as well, listeners finally realized just how pedestrian and un-pretentious Weezer really are. We like our rock stars arch and otherworldly – bestowing the gift of fire to our unendowed minds – but Weezer are content to just grunt along with the rest of us cave people.

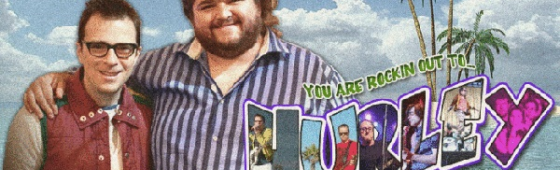

What makes Hurley an interesting new album (apart from some typically memorable tunes) is Cuomo’s new reliance on collaboration. The record features some choice guest writers (Ryan Adams, Desmond Child, Linda Perry, and Mac Davis amongst others) and as a result, is less pinned down by the front man’s narrow pop vision. Only two of the new tracks are solo Cuomo compositions – the deceptively nostalgic first single “Memories” and album highlight “Unspoken,” which starts as a modest acoustic ballad and crashes into one of the band’s hardest rocking outros. These are some of Weezer’s most open-ended, identifiable songs since probably The Blue Album. If anything will bring back their early fans (including this author), this is it. More likely, as Klosterman opines, Weezer are just doomed to frustrate fans forever. Deep down, I think you’ll find that Weezer’s grizzled old pep squad secret enjoys the constant grappling – though Rivers Cuomo, I bet, hasn’t entered any of us into the equation.

Hurley is available in record stores and online music services now.