Creative Commons Interview: Amanda Palmer — I Can Spin A Rainbow0

Posted In All Things SG,Art,Blog,DIY,Entertainment,Favorites,Interviews,Music,SG Radio

Amanda Palmer is in the process of redefining the nature of artistic freedom. Having escaped the gilded shackles of her major record label, she famously made her 2012 album, Theatre Is Evil, with the help of 24,883 fans who crowdfunded the recording via Kickstarter to the tune of $1,192,793.00. However, the hype surrounding the record-breaking fundraiser almost suffocated the album, as the media focused on the money rather than the artistic merits of the music — a huge shame given that it’s undoubtably one of her best.

Seeking a less transient form of funding that would embrace one of Palmer’s greatest assets, her relationship with her fans, in March, 2015 she joined Patreon. The alternative crowdfunding platform helps creators fund their work via a subscriber base of patrons who are either charged monthly or per item created (Palmer chooses to charge per “thing”, since it allows her to take time off guilt-free). In the two years since she joined, Palmer’s incredibly loyal fanbase have helped her become one of the top 3 content creators on Patreon by number of patrons. At the time of writing, Palmer has 9,386 patrons who give her a total of $36,598 per thing.

This has bought Palmer an incredible amount of freedom to create what she wants, when she wants. But with it comes a new set of constraints and responsibilities — many of them self-imposed. Because this form of artistic funding is so new (albeit that it’s based on a concept that’s as old as the ages), Palmer is still in the process of creating her own rules.

On May 5, 2017, her latest Patreon-funded project, I Can Spin A Rainbow, will be released into the ether. The haunting and heartbreakingly beautiful, atmospheric and melancholy album is a collaboration with one of her heroes, Edward Ka-Spel, the co-founder and frontman of The Legendary Pink Dots. The record was recorded in the UK at the Essex home studio of Palmer’s friend Imogen Heap.

I caught up with Palmer by phone to talk about the creative process and the challenges that come with the freedom of patronage.

Nicole Powers: I first saw you on June 30, 2007 at the Greek Theater with the Dresden Dolls on Cindy Lauper’s True Colors tour. It’s a very special year for us. We’re celebrating our ten-year anniversary.

AP: Oh. Awesome… I remember that tour very well. It was a total hodgepodge of amazingness and weirdness.

NP: You’ve had a fascinating journey since then. I was just watching a 2005 documentary on the Cloud Club [a residential artist commune based out of a brownstone in Boston where Palmer lives and where her band The Dresden Dolls was nurtured]. Do you miss those days?

AP: I still have that apartment. It hasn’t changed a bit. Actually, I’m driving there on Sunday… I mean, the days have definitely changed. I have a child and a husband and a house out in the country now, in addition to my bohemian apartment. Philosophically, I think it’s important not to spend a lot of time missing things. There’s too much going on right now for me to think that it’s a good idea to spend energy on those things. I loved my free-wheeling, bohemian existence, but I also wouldn’t want to be stuck in it forever. It would get stale.

NP: When I last spoke to you, in 2009, it was just after “Oasis” had been released. The song was based on very disturbing events in your life that happened when you were 17, and you spoke about how you sought solace in your favorite band, The Pink Dots. It’s wonderful that things have come full circle and you actually get to work with your hero. How did that come about?

AP: Its original seeds were planted ten years ago, probably. I’ve been in touch with the band ever since I was a teenager. When I was 20 I went out on the road and did merch for them in Germany for a couple of days. I knew them and they knew me, as people. They did a tour opening up for the Dresden Dolls in Germany in the mid-2000s — it was probably 2006. During that tour I floated the idea that it was on my fantasy list to someday collaborate on a record with him. He said, absolutely, someday, let’s do it.

In the list of projects that I wanted to do before I died, it was up there towards the top, along with making a record with my dad. I actually knocked off two Bucket List records in one year — I’m really proud of myself. And they couldn’t be more different. I made this super sweet, sincere, fancy guitar and piano record with my dad, and this album with Edward is completely different — a completely different mood, much more electronic. Maybe there’s also something important in my life; having a child and recognizing my various fathers in various incarnations.

NP: I was reading an interview that you did a while back where you spoke about the internal battle that you have between musical inspiration and meditation, and how often very complete ideas came to you when you’re alone during your practice. How does that work when there’s another person in the room? How did the actual creative process work between you and Edward?

AP: It’s a fantastic question, because I didn’t know how it was going to work when I went into making this record with Edward. Because I’m not a co-writer. I’ve always been a real lone wolf as a songwriter, mostly by choice. Because, for me, songwriting is such an incredibly intimate, personal act that the idea of doing it with someone else doesn’t make any sense to me — as much as it would make sense to do anything. So I was nervous because I just didn’t feel like a seasoned co-writer and collaborator, whereas Edward has made records with tons of people.

For that reason, I just showed up completely open-minded and ready to work — ready to write and ready to do anything. I brought old pieces of things, and I brought little bits of text, and I brought voice memos, you know, sung to myself on walks five years ago. I just brought a junk box of interesting bits. Edward had a similar pile of thoughts and fragments and we just played a game of creative ping pong. Sometimes he would start the ball rolling and he would give me a piece of text and I would try to fit it into some kind of arrangement with the piano. Sometimes I would just sit and play something and he would dream up and imagine a story to go on top of it.

As I imagined — as I feared even — it was incredibly intimate, personal co-processing. You have to have an immense amount of trust and respect for someone to sit around and go to your vulnerable, creative place. But Edward and I had such an immense amount of respect for each other that it worked. He really taught me to be a lot braver about doing my process in front of another person. I may be not afraid to walk around naked in public, but I’m actually very afraid to write songs in front of people.

It just feels so incredibly emotionally naked, to sit there writing lyrics, and chucking them out, and futzing with melodies, and playing wrong chords. It’s just something that I’m really only used to doing alone in a room by myself, so to do it in front of someone else felt scary and thrilling — and ultimately really rewarding because what we got out the other side was a record that we’re both so, so proud of.

NP: I imagine too, when you’re working with another person, it’s hard to hide behind abstraction. When you’re working on something that’s difficult for you to deal with in a song, you can be abstract about it — you know what it means, but you leave the world to interpret it. But, when you’re bringing an idea in a room to share with another human being and you’re going to work on it together, I guess you actually have to explain what the abstraction means.

AP: Either that or you have to not question the other’s poetic motives. We didn’t have to discuss and dissect every single lyric and every single adjective. We didn’t always question each other’s dressings, you know? We wrote in a way that made sense, and made sense for that particular song.

One of the things that I loved so much about writing with Edward is he actually rewound me back to a songwriting space that I was in more in my 20s where I had a lot more dressings and opaqueness in my lyrics… The first Dresden Dolls record, there are some songs on that that are just impossible to understand unless you’re me — and even if you are me. Fast-forward 20 years from the writing of some of those songs and the material that I’m writing now, some of it is so incredibly literal and soapy, which is wonderful. It is its own skill to write a good, easily digestible, literal song, but I’ve really strayed away from my more loose, poetic songwriting. It was almost like working with Edward gave me a hall pass to go straight back to 19 and write the way I used to write, especially when I was under a heavier Pink Dots influence. It was always better to say things in a way that could be interpreted six different ways than directly.

NP: How long did it take you to find your groove working together? And what song did you find that groove on?

AP: Funnily enough, it took us five fucking minutes to get comfortable with each other. There was just so much love in the room — especially since our first attempt to make the record, actually our first couple of attempts to get together, were torn apart by acts of god. Our second real legit try to get together involved me showing up at Edward’s place and on day two getting a phone call that I had fly back to the States to be at a friend’s deathbed. It was very ill-starred. By the time we actually were sitting in a room together, having tried for so many years and having such a close call, we were just so excited to finally get to work after so much had already gone down — we were already really emotionally attached. The interesting thing about our first day of work is that the day before that had actually been a year before that and I was eight-months pregnant and sobbing in Edward’s arms at a train station that I had to go watch my friend die. So we had become quite close and we just slipped into a groove very easily. Edward’s really easy to work with.

I’ve luckily never been in a nightmare collaboration. I’ve been blessed with really delightful, easy to work with collaborators, from Jherek Bischoff to Jason Webley and all of the other people that I have arranged with and co-written with in the last ten years or so. But, with Edward, there is an incredible sweetness about him. He is really not self-conscious about his process and he has no ego whatsoever. The two of us just got to amuse, and impress and delight each other. Why else would you create a record together?

The older I get, and the more projects I do, the more concerned I am about the process itself being enjoyable. When you’re a professional musician you realize that that’s actually the content of your life. The desire to work with good, compassionate collaborators starts to take importance over whatever is going to come out the other end of the tube. That starts to matter less and whether or not you want to sit down and have dinner with this person starts to matter more — because this is your life. You’re like, oh right, if I don’t like the people I’m working with, my life is going to be miserable.

NP: You once said, “A perfect song is a captured moment of inspiration barely touched.” On this album, what song would you say most embodies that?

AP: Probably “The Clock At The Back Of The Cage,” which is far and away my favorite track on the record. I had the general idea for it brewing the entire time Edward and I were working on the record. I even mentioned to Edward that I wanted to write a song like it. It was just an unformed, fetal-being just bouncing around in my brain as we worked. Then Imogen had this beautiful glockenspiel in her studio, and it was like the song was just waiting there to come out one night. I grabbed the glockenspiel and wrote the opening part on the glockenspiel thinking that that would just be a cute introduction and it would probably be a piano song, and it would probably have Edward’s looping, and it would probably sound a lot like the rest of the record. But it was such an emotionally painful song that it just wanted to stay sounding small. So we left it that way. But then we put that really foreboding underbelly of sound beneath it. Sometimes you finish a song and you just know that you have a completed, perfect piece of work — and that’s the way I felt after that one.

NP: What was the nugget of inspiration that kept visiting your head and not leaving you?

AP: I’m not sure I can discuss that one… Let’s just say that it is a very, very personal song and leave it at that.

NP: Fair enough. When we last spoke, you were looking ahead to life beyond a major label. Since then, that philosophy has come fruition, first with your blockbuster Kickstarter, and now with Patreon, and your TED Talk, The Art of Asking, which you’ve expanded into a book. How do you think your process has changed from making a record for a label versus making a record for your fans?

AP: It’s actually quite an easy answer, which is, being on a label never changed my process. If anything, getting off the label gave me an immense amount of freedom — maybe too much freedom, because I was just following every last whim for so many years. I was just drunk on my ability to create music and put it out, especially given the digital free-for-all of the internet. Knowing that I could make music and literally put it out that day was so delicious after being in the golden handcuffs of a major label.

Sometimes I look back on my musical track record post-Dresden Dolls and it just looks like an insane patchwork, a random-ass shit show with no forethought. And that’s exactly what it was. But I was so fucking happy. I was just like, I want to make a record of Radiohead covers, I want to make a fucking weird-ass musical concept record about conjoined twins, I want to do this, I want to do that — and then I would just do it.

It was so delicious to be able to do what I wanted that I didn’t care. Then I sort of set all of my serious songwriting in one box and I collected it all together for Theater Is Evil, which is the Kickstarter record, which I still think is far and away one of the best records that I’ve ever made. I am just so, so proud of it. Then, you get this interesting twist in the story; I was convinced that because I captured everybody’s attention because of the Kickstarter that everyone would also pay attention to the record. But, mostly, all the media discussed when they discussed me was money. That was really disheartening. That was a shitty year.

NP: I can see that that must have been incredibly frustrating.

AP: Well, amen. So, yeah, that’s one of the things that I feel is a really hard won lesson. My dialogue with my hardcore listeners, and my dialogue with the mass media and the mass internet, they are parallel conversations but they’re different conversations. And you wait six months and the landscape changes right before you, especially in terms of how things are coming out.

It’s why I am so grateful to have this group of 10,000 people who just trust me. They trust me not to screw them. They trust the fact that I’m an authentic artist and that my heart is in the right place and I just want to make work that I believe in. And that relationship is a hard won relationship. Just like the Kickstarter. It’s not something that just happens overnight because you have a hit single. It’s something that happens because you toured for years and years, and you hang out with everybody, and you prove that you’re a lifer.

I’m really proud of this space that I built where all of those people want to support me. Sometimes I can’t even really believe that it’s real — and it’s been going on for two years. In a sense, nothing has freed me up artistically as that security — of knowing that I don’t have to, all of a sudden, hop on a tour bus and tour in order to pay for a project. I will never need corporate sponsorship. I will never need to compromise because I have enough. I have enough support. It’s such a wonderful feeling as an artist to know that there are enough people there to easily float your ability to create. It’s awesome.

NP: It has also broken the mold that you have to have an album, with three singles for the label to market, to have a “thing” that someone will buy. One of the lovely examples of that is your “Angel Gabriel” recording and video that you released over Christmas. I could imagine that if that had been in the context of a major label, they would have wanted you to do a whole album of schmaltzy Christmas songs and you would have lost the entire point of it. That song and video is so much more of a statement on its own than it would be if it was buried amidst ten other songs that you were forced to throw together to make a thing that a major label would accept.

AP: Yeah. Exactly. It’s really wonderful deciding what to do with everybody’s money as well, and just challenging myself to be as ethical as possible. Because on the one hand I have this wonderful freedom to know that I can sit down at the piano at any time, make arrangements anytime, write music anytime, and know that I have a guaranteed audience, not only to listen to it, but to pay for it. But on the other hand, I feel this mighty responsibility that I don’t want to let people down and I want to spend their money ethically, you know? Because there I am, basically doing a bunch of artistic curating. I’m deciding who to hire, and who to engineer, and who is going to photograph, and who is going to video, who is going to design the sets. There is something really nice knowing that that’s not the label’s money, but it’s the people’s money. As I’m hiring a whole bunch of artists in Cuba, who are really grateful for the work, I love that that money is coming from my fans and not from some corporate boss in the sky. It just feels really good.

NP: You spoke earlier about the parallel conversations you have between your fans and the mass media. Obviously you have a very special relationship with your fans, and sometimes a comment that you make, that is completely understandable within the context of your fanbase, will get completely taken out of context by the mainstream media. For example, the whole “Trump will make punk rock great again” thing. I absolutely know what you’re trying to say, but seeing it taken out of context for clickbait was kind of offensive. I imagine you don’t want to self-censor, so how do you deal with that?

AP: I just work on the running assumption that people are going to misunderstand me and I try not to give a shit, honestly. And as far as Donald Trump making punk rock great again — we should be so lucky. That was more of a call to my fellow artists that we need to up our game in the face of this insanity. I hope we all do.

NP: It’s so hard to live in a world where we’re seeing hard won rights being taken away from us and society regressing rather than progressing. Do you feel more of a sense of urgency now that you’re a mother to try to shift things in the right direction?

AP: No. I have always felt a sense of urgency for change. In fact, if anything, having a child has forced me to slow down and be more mindful and smell more flowers with my baby. Because his childhood feels incredibly precious to me. He’s not going to appreciate a mother who is spending too much time trying to be a warrior hero. I mean, I will do what I can do, but I also sometimes feel like the biggest gift I can give to the world right now is being a good mother to my child. As hokey as that may sound, it’s how I feel.

Catch Palmer and Ka-Spel on tour in the United States and Europe from May 17 thru June 18, 2017.

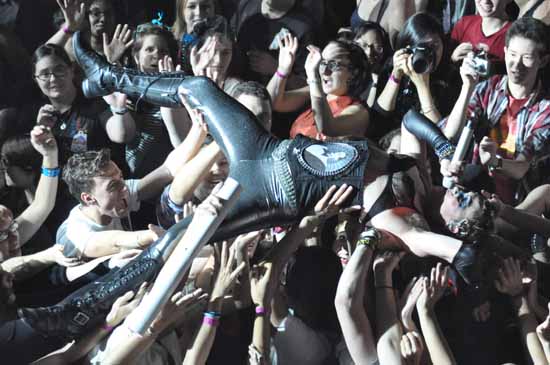

Photos taken by Nicole Powers at Webster Hall in NYC on September 11, 2012.

Related Posts

Amanda Palmer — Theatre Is Evil

Amanda Palmer — Evelyn Evelyn

Amana Palmer and Neil Gaiman Live

Amanda Palmer — Rebel With A Cause

This interview has been edited for length and clarity, and is published here under Creative Commons License 4.0. It may be reposted freely with attribution to the author, Nicole Powers, and this notice.