Fiction Friday: The Killswitch Review – Chapter One, Part Three2

Posted In Blog,Books,Entertainment,Fiction,Geek,Internuts

by Steven-Elliot Altman (SG Member: Steven_Altman)

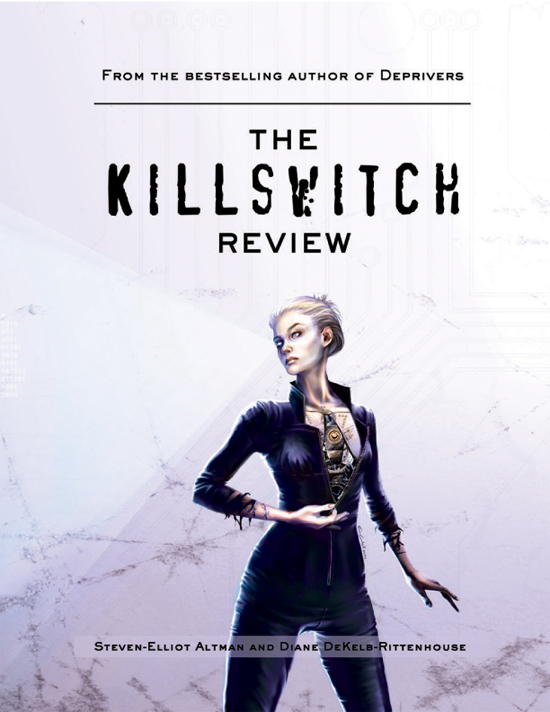

Our Fiction Friday serialized novel, The Killswitch Review, is a futuristic murder mystery with killer sociopolitical commentary (and some of the best sex scenes we’ve ever read!). Written by bestselling sci-fi author Steven-Elliot Altman (with Diane DeKelb-Rittenhouse), it offers a terrifying postmodern vision in the tradition of Blade Runner and Brave New World…

By the year 2156, stem cell therapy has triumphed over aging and disease, extending the human lifespan indefinitely. But only for those who have achieved Conscientious Citizen Status. To combat overpopulation, the U.S. has sealed its borders, instituted compulsory contraception and a strict one child per couple policy for those who are permitted to breed, and made technology-assisted suicide readily available. But in a world where the old can remain vital forever, America’s youth have little hope of prosperity.

Jason Haggerty is an investigator for Black Buttons Inc, the government agency responsible for dispensing personal handheld Kevorkian devices, which afford the only legal form of suicide. An armed “Killswitch” monitors and records a citizen’s final moments — up to the point where they press a button and peacefully die. Post-press review agents — “button collectors” — are dispatched to review and judge these final recordings to rule out foul play.

When three teens stage an illegal public suicide, Haggerty suspects their deaths may have been murders. Now his race is on to uncover proof and prevent a nationwide epidemic of copycat suicides. Trouble is, for the first time in history, an entire generation might just decide they’re better off dead.

(Catch up with the previous installments of Killswitch – see parts ONE and TWO – then continue reading after the jump…)

“Haggerty, where ya’ been?” Tanner grumbled as they entered the viewing room, looking up from his breakfast. “Diddling your assistant? We had a double press over an hour ago.”

Elsa took a seat at the main switchboard and began downloading data, ignoring Tanner’s comment. Haggerty envied her ability to remain unmoved. After decades of ignoring it himself, he’d lately found Tanner’s habitual, juvenile crudeness unbearably irritating.

If Jason Haggerty tried to live up to the ideal of what a Conscientious Citizen should be, Mitch Tanner seemed intent on living down to the worst excesses associated with the status. Haggerty didn’t like Tanner, finding in him the extreme example of everything that was wrong with the majority of people who’d been CCs for more than two decades. He dosed too much in his off time, bitched too much when he was on, and had been campaigning to get Elsa into bed almost from the moment she’d become Haggerty’s assistant. He also went in for plastiche to the point of absurdity. Nobody went much past thirty without at least one visit to the best plastiche parlor he or she could afford, but Tanner chose to look like a JC rather than an adult, and acted like he was no older than he looked. He was ninety-two playing at twenty-two, and not very convincingly. But whatever Haggerty thought of Tanner’s perpetual adolescence, he had to work with the man, if only for the rest of the day.

A quick look at what Tanner was eating, greasy cubes of cloniform beef from the cafeteria dispensary, was enough to turn Haggerty’s stomach. Some of the grease had made a bid for freedom on its way to Tanner’s mouth, and got as far as his chest; two small dark spots marked his regulation grays, which the self-cleaning fabric would eliminate within half an hour. At the moment, though, they remained revoltingly visible.

“Do you have a clue how they prepare that stuff?” Haggerty asked, indicating the plate of food.

“Nope,” Tanner said. “As long as they’re doing the preparing and not me, I don’t really care.”

“There hasn’t been a live cow on the planet for half a century,” Haggerty pointed out. “What they call meat in that swill was culled from a one-hundredth generation clone, grown in a nutrient tank, packed in fake gelatin, flavored with synthetics, and then saniwaved” — which was the reason Haggerty, despite his love of rare steaks and thick burgers, reluctantly followed a vegetarian diet.

“Jeez, Haggerty,” Tanner said, forking up another mouthful of cloniform beef, “you sound like that Code Six guy who’s supposed to be holed up in the desert someplace. What’s his name? Cody?” Tanner scrunched up his face in concentration. “Bodey? Brody?”

“Tomas Yosif Svoboda,” Elsa supplied.

“Yeah, him,” Tanner said. “The back-to-nature nut.”

Code Six was one of the “blue codes,” police designations for threats to public health and safety that required the intervention of law enforcement officers, in this case designating that the person causing the disturbance appeared to be mentally defective and should be approached with caution. Haggerty dimly remembered headlines from decades ago regarding this man, Svoboda — a physicist who supposedly found God, denounced society and founded a cult of subversives called — what was it — the “Indivisibles?”

Tanner lifted his fork to his mouth and another scrap of breakfast hit his grays, making a third spot bloom on the cloth. Haggerty’s mouth tightened. Like so many others, Tanner didn’t look deeply into the nature of things, or care about anything unless the telemonitor warned him to. Perhaps Tanner’s failure to see below the surface was the reason he was merely a trace and dispatch operator, while Haggerty was a reviewer.

“Who and what?” Haggerty asked now, giving up speculation and turning to the job at hand.

He stepped into the pulpit and powered it on. Elsa’s fingers blurred in motion on the transparent board. Data streamed before Haggerty: holo-reps of both pushers, one male, one female, their lives in coded bytes listing below them.

“The dearly departed,” Tanner quipped. “His name was Gustavo Nyuga, one hundred and four, and she was Maria-Christina Rosenberg, one hundred and thirty.” Tanner smiled nastily. “Guess he liked older women.”

To the eye, they both seemed nubile, ageless. The remark was another of Tanner’s crudities: with people living well into their second century and no one looking much over thirty, age gaps between couples were commonplace. What did a few decades matter when everyone had so many of them to look forward to?

“He was a retired investment banker; she was his client, then boss, and then lover,” Tanner continued.

“When and where?” Haggerty asked, moving into the scaled continuous-update holo-rep of the cityscape.

“Oh-eight forty-two,” Tanner read aloud. “The Hodkins Building.” An amber pinlight fixed on a Southside compartment. Haggerty knew the building; he’d been assigned there on a number of occasions. “Looks like they pressed together. Very sweet,” Tanner said.

Who, what, when, and where duly answered, it was Haggerty’s job to find out the why and make sure it was clean. The how he knew all too well.

“Elsa, code us last rites and warrants and get me a thermos of coffee, won’t you?” he requested as he returned to the pulpit.

“Sorry folks, this is a press scene.”

The man had to be new on the job, not to distinguish between the gray suits of ordinary citizens and their regulation grays. Haggerty flashed his BBI identiplate and the officer, with an embarrassed apology, waved them on.

The door was ajar. Inside they found a well-dressed man seated calmly on an esplanade couch drinking a glass of blue liquid, maybe KeepAwake. Dark-haired, tanned, handsome in that bourgeois way that plastiche seemed to have made everyone’s birthright, he placed his drink on a coaster on a delicate antique end table and rose to greet them.

“The name’s Primrose,” he said. “Haggerty, right?”

Haggerty reached to shake hands. “You’re the adjuster? Never seen you before.” He’d also never seen anyone who’d chosen to keep his physical appearance at early middle age, though he knew the trend was gaining popularity with some businessmen. Primrose sported a frost of silver at each temple, stark and handsome against his dark hair, and the barest suggestion of lines around his eyes. His athletic build had a hint more solidity than the usual thirty-year-old look. Primrose’s look was distinguished, striking, sophisticated, intended to convey authority and experience — invaluable in an adjuster’s work, Haggerty thought.

“Just got assigned to NewVada,” Primrose said. “Transferred from New York.”

“You must be excited,” Haggerty said.

Primrose appeared confused.

“The game?” Haggerty added.

“Oh, the Superbowl. I won’t be there. I’m not much of a football fan,” Primrose said with a self-deprecating smile. “Don’t appreciate violent sports.”

Haggerty nodded. He had his own reason for not being there, beside the fact that tickets cost a small fortune and were near impossible to come by. He’d shared a love of football with his father, and had painfully let it go in his absence. Pressing the night before the big game would itself be an act of defiance for Haggerty. The fact that NewVada was finally a contender made it all the more ironic.

“Mind showing us the press site?” he asked Primrose.

“This way.”

Primrose’s swaggering walk suggested confidence, another asset in an adjuster. Who wanted to leave their final affairs in the hands of someone who didn’t have absolute faith in what he was doing? But, Haggerty thought, Primrose overdid it a bit. Like Tanner’s love affair with puberty, Primrose’s idealized middle-aged man rang false. From the clothes he wore and the jewelry he affected, Haggerty read Primrose to be not much older than the appearance he maintained, a youngster of fifty or so. Most likely he was an up-and-comer with great prospects but a minimal track record in his field, for which his appearance was calculated to compensate. He couldn’t blame Primrose for trying to gain advantage. Everyone started someplace.

He really is young, Elsa told Haggerty through their link. I can tell.

So can I, Haggerty sent back.

Primrose led them into the bedroom, a healthy-sized chamber nearly eight-by-eight, half the size of Haggerty’s but still indicative of wealth, as were the room’s furnishings. Before he’d pressed, Nyuga had indulged a taste — his or his lover’s — for antiques. Real wool carpets covered the floor; bureaus, end tables, and armoires of genuine wood stood against the walls. There were lighting fixtures on tall, elegant poles with fluted crystal glass bowls to deflect the illumination — torch lamps, Haggerty vaguely recalled, his mother had owned one, inherited from a great-aunt. The bed was not the standard platform but a carved fantasy designed to look like a Russian sleigh from at least three centuries back. The wood was natural, though Haggerty couldn’t say from what kind of tree, and against the dark frame a set of mauve silk bedclothes had been twisted by passion, not slumber, and heaped together like discarded flower petals. Drool-tinged blood was evident on one pillow, urine and fecal stains on the sheets — typical evidence of a press. One KV unit lay half hidden beneath a coverlet; Primrose pointed out the other one on the floor, under the bed.

Haggerty cleared his throat. “Do you have the DCs?”

“Right here,” Primrose said, holding up his com and hitting the recall codes. He withdrew the two strips of plasticine the com disgorged. “Do you have the warrants for the boxes?”

Haggerty nodded, following suit with his own com. The two men exchanged documents that were neatly encoded on plasticine cards. Haggerty scanned the death certificates, observing that they were affixed with the proper coroner’s seals, then asked, “How long since the bodies were removed?”

“Half an hour,” Primrose said. “They took all the necessary samples. The detective, I believe his name was —”

“Woyzeck, I know him,” Haggerty interrupted. “He called it a love-spawned clean double, pending our review.”

“His exact words,” Primrose said.

“Okay, let’s do it,” Haggerty said. “Record on.”

Elsa leaned against the bedroom door, casually smoothing blonde hair from her face and folding her arms. “Recording,” she said.

“Eulogic proceedings for Gustavo Nyuga and Maria-Christina Rosenberg. Jason P. Haggerty, representative for BBI, presiding.”

“Oliver Wendell Primrose, adjusting agent for the insurance firm of Cromwell and Sons, prepared to review,” Primrose added in a more officious tone.

Haggerty went to the bed, pulling on black duratex gloves. “Elsa,” he said, “please note: By the authority vested in me by legal warrant of the State of Nevada, I am taking possession of, and responsibility for, two KV black button units that are, to the best of my judgment, the property of BBI and assumed to be the devices of record assigned to the deceased.”

“So noted,” Elsa responded.

Haggerty picked the first unit off the bed and read out the serial number engraved on the casing, then got down on his knees, retrieved the second unit, and repeated the process.

“Serial numbers confirmed as those registered to the deceased,” Elsa said a few seconds later.

“Units appear fully intact and previously armed,” Haggerty continued. “Tabs popped clearly indicate that both buttons have been pressed.” He tipped the boxes up for Primrose to inspect.

Keeping a safe distance, Primrose eyed the tabs and called, “In my best judgment, I confirm that both buttons appear to have been pressed.”

Post-press, the units were, at least in theory, toxin-free, but Haggerty was careful as he handled them, anyway. BBI protocol required that he not put the theory to the test. He brought them over to Elsa. “Mind closing the curtains?” he said to Primrose, who located the console and dialed them shut.

Elsa stood motionless against the door, waiting for Haggerty to reach her. She gave him a look; he supposed she’d smelled the celtrex lacing the coffee on his breath. As he handed her the first unit, she unfastened the tab at the collar of her jumpsuit and pulled the zipper down to her waist in one smooth motion. Primrose watched with an avidity bordering on the salacious as she pressed her thumb hard against her sternum, snapping open her breastplate and exposing her ported upload center, then deftly inserted the unit.

“Analysis?” he asked.

Elsa was silent a full minute, then, “Serial numbers as previously confirmed. Residue on unit confirmed as a BBI toxin. Prints on unit confirmed as belonging to the registered owner. It is established that this is the device of record for Maria-Christina Rosenberg.”

“Play recording with full room projection,” Haggerty said. “Adjust for the light.”

Behind Elsa’s irises, twin beacons whirred into motion, projecting onto Haggerty’s face. He stepped aside. A duplicate holo-image overlaid the room, with the notable inclusion of Gustavo Nyuga and Maria-Christina Rosenberg nude in bed, KV units in hand. Hers was armed; tears wet her cheeks as the soft male electronic voice announced, “Recording,” and went on to give the date and time. The unit cast a violet light across the couple’s bare skins.

Primrose stood mesmerized, as if this were his first post-press viewing. Haggerty had encountered that sort of prurience before. Some adjusters never got tired of the show; it was almost indecent. It seemed to Haggerty that the final moments of the deceased should be observed solemnly, with respect. He turned his attention back to the review.

Gustavo Nyuga took Maria-Christina in his arms, peering over her shoulder as he armed his unit. “Recording,” it droned, bathing the curve of her back in pale green light.

“Quickly, Gustavo, before I change my mind,” she wept. “I love you forever.”

“God, I love you too,” he said, and pressed. She moaned when she heard his unit pop. Then hers popped as well.

Her unit continued to record as they crumpled against each other onto the pillows, euphoria in their eyes. Their bodies trembled and gave a final spasm as their hearts seized simultaneously. Looking at them, Haggerty wondered if having someone to press with made it better. Was there comfort in being so close to someone that the decision could be made, and acted upon, jointly?

Primrose stood by the bed, so near he looked comically like a participant in the scene, his hand to his mouth as though holding something back. Nausea? Excitement?

Haggerty didn’t want to know. “Judgment,” he called.

Primrose took a breath. “Cromwell and Sons declares the cases of Gustavo Nyuga and Maria-Christina Rosenberg to be legitimate presses, their actions apparently the result of joint bankruptcy and inability to secure future income. As neither Mr. Nyuga nor Ms. Rosenberg has any living relatives or heirs, the settlement of their affairs will be posted to the State.” After, of course, Cromwell and Sons took their cut, Haggerty thought. Certainly there were enough antiques in the bedroom alone to cover the normal fees, dues, and charges such firms exacted for their services, before the client’s creditors and heirs — in this case, the State — got to wrangle over what was left.

Haggerty had listened to Primrose stoically. Properly speaking, they ought to have waited for the second review before signing off on both cases. “In the case of Maria-Christina Rosenberg, death by press judged clean,” Haggerty pronounced. “Stop projection.”

The couple vanished. Elsa removed the unit, and Haggerty took it from her, handing her Nyuga’s, sliding Rosenberg’s into a minthizine case for transport back to headquarters. Elsa had already run the analysis, confirming the second unit as Nyuga’s device of record, and begun uploading his final recording, when Primrose spoke.

“Don’t see any need to play the other recording,” he said, fetching his drink from the end table.

Elsa looked at Haggerty. I don’t understand why adjusters are always so impatient, Jason, she sent across their link. Shall I proceed?

Elsa was right: adjusters never wanted to hang around a press scene once the unit was reviewed. They preferred to have the formalities handled as expeditiously as possible so they could go about the business of securing assets, finalizing arrangements, and determining their percentages. A year ago, Haggerty would have ignored Primrose’s comment and told Elsa to proceed with the projection. Adjusters might not like the additional delays and attrition of assets that accompanied the exceedingly rare finding of a criminally manipulated press, but Haggerty had always been scrupulous in carrying out his duties. As a result, he found those exceedingly rare criminal manipulations a less conscientious reviewer would have missed.

But he was a different man today than he had been a year — a lifetime — before. Fewer and fewer manips had been found over the past few decades. These two clients certainly had reason to press and — unless Governor Benfield had suddenly acquired a passion for torch lamps — no heirs to benefit from hurrying them along their way. What was the point of looking further?

It’s all right, Elsa, Haggerty sent across their link. I think the first projection told us everything we need to know. Aloud, he said, “It’s clear what happened. Record epitaph: Regarding the case of Mr. Gustavo Nyuga, one-hundred-four, and Ms. Maria-Christina Rosenberg, one-hundred-thirty, consecutive presses observed and both judged clean. Eulogic proceedings convened on March eighth, Twenty-one-fifty-six, by BBI senior agent Jason P. Haggerty. Life insurance settlement to be placed in trust to the State.” Formalities taken care of, he gestured for Elsa to return the second unit. “Go ahead and open the curtains,” he told Primrose, and secured the second discharged unit in another minthizine case.

The other man dialed the curtains back open, rubbing his eyes as sunlight flooded the compartment. “Is that all?” he asked Haggerty, pulling out his com and flipping it open to record the BBI agent’s verdict in the appropriate files.

“Yes,” Haggerty said, concealing his distaste for Primrose’s cavalier attitude. “That will be all as far as BBI is concerned.”

Primrose closed the com again and put it away. “Nice working with you, Mr. Haggerty.” He extended his hand, realized Haggerty was still wearing the duratex gloves, and settled for a nod. “Have a good day.”

Primrose left the room.

Haggerty went into the bathroom and ordered the sink, “On, hot.” Elsa helped him out of the gloves, which she put in a minthizine biohazard bag, before they began sterilizing their hands as BBI protocol required once discharged units had been contained.

“Jason, I have a question,” she said, looking up from her cleaning.

He saw that she was addressing his reflection in the mirror, and found it odd. “What’s on your mind?” he said.

“The decision those two people made to press together. It was premeditated, wouldn’t you agree?”

Haggerty nodded.

“Please explain to me why two healthy people, in no apparent jeopardy, would decide that they have had enough of life at precisely the same time.”

Haggerty stopped scrubbing and looked at her reflection, perplexed. They’d worked together a long time, reviewed hundreds of double presses together. Why this question now? He thought about how to summarize, knowing that inevitably his answer would fall short of acceptable to her logic board. He knew Elsa was perpetually reprogramming herself, to better understand the nature of those she served, but this was a difficult query, perhaps important to her development. He selected his words carefully.

“Two people can grow together, share so much together, have such a commonality, that they begin to make decisions as one,” he explained, or hoped he did.

Elsa gazed into the mirror, unblinking. “So if the drive to press is based primarily in despair, I should assume they shared the exact same level of despair?”

Haggerty toweled his hands, aware he was not doing a very good job of explaining. “Sort of,” he said. “Let’s say they were committed to each other and circumstances led one of them to decide that pressing was the right choice. Even though the other may not have been suffering the same level of despair at that moment, the strength of their commitment, coupled with the fear of being separated from each other, the person who is the main reason and purpose for living, compounds the despair.” Haggerty scratched the back of his neck. “That could bring them to a decision to press together.”

“Despair by osmosis,” Elsa stated flatly.

“Something like that. Does this shed any light on the human condition for you?”

“I’m going to digest it,” she said, using one of the phrases Haggerty employed in rare moments of uncertainty — or, more usually, to mask defiance toward his superiors. “I’ll run it parallel against previous input and observe the variable shift.”

Haggerty smiled, ever astonished at her desire to learn, to understand. The bulk of androids produced these days were suited only for the most menial or dangerous work no human wanted to do. Intelligent, intuitive androids like Elsa were few and far between, too expensive to produce in quantity, the jobs they were suited for too badly needed by the burgeoning human population. Haggerty took the extra time and effort with her because she had, in many ways, been raised by him, a standard perk in his department long before the impact of androids in the workforce had become an issue with the unions. Her personality, distinctly machinelike and artificial when she’d arrived to replace the earlier model he’d been assigned, had evolved over time, largely in response to his influence. While she was, perhaps understandably, a little too protective of him and inclined to nag, he was happy to have had a hand in her development.

“You do that,” he said.

Steven-Elliot Altman is a bestselling author, screenwriter, and videogame developer. He won multiple awards for his online role playing game, 9Dragons. His novels include Captain America is Dead, Zen in the Art of Slaying Vampires, Batman: Fear Itself, Batman: Infinite Mirror, The Killswitch Review, The Irregulars, and Deprivers. His writing has been compared to that of Stephen King, Dean Koontz, Michael Crichton and Philip K. Dick, and he has collaborated with world class writers such as Neil Gaiman, Michael Reaves, Harry Turtledove and Dr. Janet Asimov. He’s also the editor of the critically acclaimed anthology The Touch, and a contributor to Shadows Over Baker Street, a Hugo Award winning anthology of Sherlock Holmes meets H.P. Lovecraft stories.

Steven also bares ink on his body, and is bi, as in bi-coastal, between NYC and LA. He’s currently hard at work writing and directing his latest videogame Cursed Love, an online free to play gothic horror RPG from Dark Hermit Studios, set in Victorian London. Think Sherlock Holmes, Jack The Ripper and Dorian Gray mercilessly exploit the cast of Twilight. Friend Cursed Love (Official Closed Beta) on facebook and you can have fun playing out this tawdry, tragic romance with Steven while the game is being beta tested!

Diane DeKelb-Rittehouse spent several years in Manhattan as an actress before marrying her college sweetheart and returning to the Philadelphia area where she had been born. Diane first worked with Steven-Elliot Altman when they created the acclaimed, Publisher’s Weekly Starred-Review anthology The Touch: Epidemic of the Millennium, in which her story “Gifted” appeared. Diane has published a number of critically acclaimed short stories, most notably in the science fiction, murder, and horror genres. Her young adult fantasy novel, Fareie Rings: The Book of Forests, is now available in stores or online.

Interested in buying a printed copy of The Killswitch Review? Well, Steve’s publisher Yard Dog Press was kind enough to put up a special page where SuicideGirls can get a special discount and watch a sexy trailer. Just follow this link to KillswitchReview.com and click on the SG logo.

Fiction Friday: The Killswitch Review – Chapter One

Fiction Friday: The Killswitch Review – Chapter One, Part Two

Fiction Friday: The Killswitch Review – Chapter One, Part Four