Fiction Friday: The Killswitch Review – Chapter Two, Part One0

Posted In Blog,Books,Entertainment,Fiction,Geek,Internuts

by Steven-Elliot Altman (SG Member: Steven_Altman)

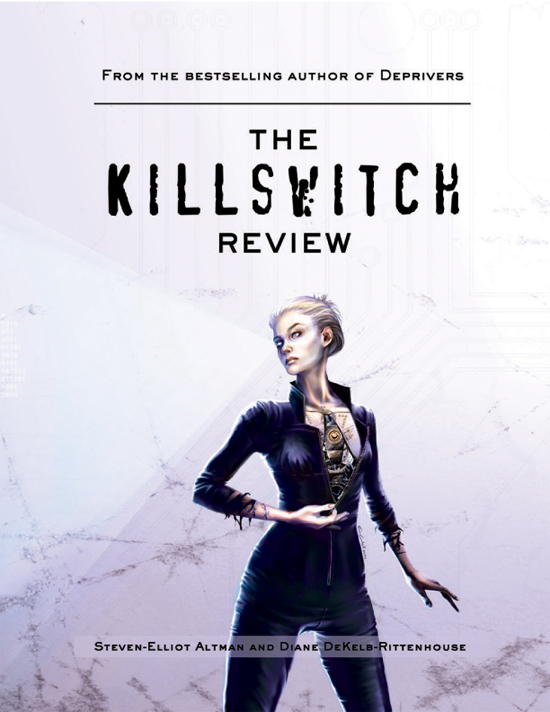

Our Fiction Friday serialized novel, The Killswitch Review, is a futuristic murder mystery with killer sociopolitical commentary (and some of the best sex scenes we’ve ever read!). Written by bestselling sci-fi author Steven-Elliot Altman (with Diane DeKelb-Rittenhouse), it offers a terrifying postmodern vision in the tradition of Blade Runner and Brave New World…

By the year 2156, stem cell therapy has triumphed over aging and disease, extending the human lifespan indefinitely. But only for those who have achieved Conscientious Citizen Status. To combat overpopulation, the U.S. has sealed its borders, instituted compulsory contraception and a strict one child per couple policy for those who are permitted to breed, and made technology-assisted suicide readily available. But in a world where the old can remain vital forever, America’s youth have little hope of prosperity.

Jason Haggerty is an investigator for Black Buttons Inc, the government agency responsible for dispensing personal handheld Kevorkian devices, which afford the only legal form of suicide. An armed “Killswitch” monitors and records a citizen’s final moments — up to the point where they press a button and peacefully die. Post-press review agents — “button collectors” — are dispatched to review and judge these final recordings to rule out foul play.

When three teens stage an illegal public suicide, Haggerty suspects their deaths may have been murders. Now his race is on to uncover proof and prevent a nationwide epidemic of copycat suicides. Trouble is, for the first time in history, an entire generation might just decide they’re better off dead.

(Catch up with the previous installments of Killswitch – see parts ONE, TWO, THREE, and FOUR – then continue reading after the jump…)

Haggerty spent the rest of the day behind his desk checking paperwork from cases reviewed by other agents and officially closing the files, grateful that the boards were clear — he couldn’t have handled another review. Maria-Christina Rosenberg’s soft sobs, the bleak despair in Gustavo Nyuga’s voice were still with him. His limit for handling emotional pain — his own and others’ — was well and truly exceeded. He could no longer deal with Tanner’s obscene glee while recounting the stats of someone who’d pressed. He would hand off any other cases that came in that day, even if it were Corbin who took them.

He reflected on the system and the part he played within it. Did presses really need to be inspected anymore? When KV units were first introduced, attempts had been made to use them for illegal purposes — fraud, even murder — and review agents were necessary. Haggerty knew this from experience. From the start of his career, he had detected manipulations, including some missed by the initial reviewer, and was proud of his reputation as one of the best in the business. But there had been nothing of importance to detect in a very long time. Second reviews, standard in the initial decades, had been reduced to random samples, then done away with altogether. The kind of paperwork check in which Haggerty was currently engaged involved catching clerical errors or mistakes in protocol. Haggerty had begun to think that meticulously reviewing the recording of every press to uncover criminal intent was a waste of time and resources. Surely a random review system provided whatever safeguards were needed to deter wrongdoers from interfering in a press.

But no one with the power to change the system was in any hurry to do so. The scrupulous reviews, the follow-up reports and analyses, were all expensive components of a lucrative process that benefited a number of parties. As long as there were insurance agencies trying to avoid paying more than they had to for as long as possible, and heirs trying to inherit more than their due, Haggerty’s and his colleagues’ skills would be required. Death by press might be government-sanctioned and BBI a subsidiary of the state’s Department of Public Health, but it was also a business.

Haggerty felt drained when his shift finally ended. He glanced around the room, satisfied that it was ready for whomever the Dragon assigned to take his place. Walking down the familiar corridor a final time, he passed the portrait of T. J. Sovereign, a young man with pale skin, dark eyes, reddish-brown hair, and a look of perpetual sobriety — the inventor of the KV unit. Haggerty had always been curious about him, but found little in the official records beyond statistics — birth date, degrees, marriage, children, employment, and when he’d invented the black box. There was nothing about the man himself, why he’d invented it, how he’d felt about the way it was used. Haggerty knew Sovereign had been one of the original directors of BBI, but he’d resigned after a mere five years, and there was nothing about what happened to him after that. He might have retired and moved to Florida, or died peacefully in his sleep; he might even have used his own invention. It wasn’t the most important mystery Haggerty had ever faced, and he was reconciled to leaving it unsolved. He nodded good-bye to old T. J. and made his way toward the exit.

“Good night, Elsa,” he called.

She was still sorting data. “Good night, Jason,” she said, looking up briefly from her viewscreen and smiling. Haggerty took a last look as she turned back to the data streams. He was going home to a compartment that could easily house two families, while Elsa would tube up to the eightieth floor and a recharging cell which — because it was the size of a coffin, possessed no interior illumination yet provided Elsa with the electrical “sustenance” she needed — the reviewers jokingly referred to as a “womb-box.” Haggerty understood that — being a machine — Elsa didn’t find such restriction objectionable. But his gut insisted she ought to object to being so confined. As far as he was concerned, Elsa had more humanity in her circuit boards than many of his flesh-and-blood coworkers, clients, and neighbors.

He stood lingering too long. Elsa noticed.

“Is something wrong, Jason?” she asked.

He scratched the back of his neck. “Not really,” he said. “Everything checking out with the decedents’ records?”

“The Nyuga and Rosenberg remains have been turned over to the mortuary designated in their wills. Their affairs are properly concluded.”

“Good work,” Haggerty said. “Good night again, Elsa.”

“Good night, Jason. See you in the morning.”

She might at that, he reflected, if she were sent with the agent conducting his post-press. He wondered if he ought to leave instructions for the Dragon about his assistant’s Personal Loyalty Chip, supposedly removed long ago. It occurred to him that, if Elsa were reassigned to Corbin, it would do the brat good to find out the hard way about the chip. Haggerty was mentally going through the short list of reviewers without android assistants, trying to figure the odds on Corbin upgrading to Elsa, when the green-eyed girl who had accosted him earlier once again blocked his path on the quad. Haggerty braced himself for a confrontation, expecting her to rail at him.

Instead, she merely said, “Why didn’t you have me arrested this morning?”

“If that’s what you want, I still can,” Haggerty said, grinning mildly, supposing that she was hoping for media coverage to help spread her message to the uninformed masses. Splintered masses would be closer to the mark. Though BBI had been incorporated nearly three quarters of a century before, many citizens, even those with CC status, were on the fence regarding the morality of the right to die. But the girl surprised him again.

“No,” she said, almost contritely. “I’m sorry I told you to cough and die.”

“It’s okay,” Haggerty said. “But what exactly does ‘cough and die’ mean?”

“It’s an old-style cracker term for when a computer program unexpectedly crashes,” she explained. “When there’s no apparent cause, like a virus or a fatal error. If a cracker makes a system crash, he’ll leave a message saying SCREAM AND DIE.”

“Is that the new lingo, ‘old-style cracker’?”

She smiled. “It’s mine, anyway.”

“Well, your apology’s accepted,” he said. “But you’ll have to find someone else to arrest you.”

“I saw you go in there twice today. You’re a button collector, aren’t you?”

The slang term always stuck, Haggerty thought ruefully. In the end he was always a button collector.

“I am,” he said. “The polite term is ‘post-press review agent’ or just ‘reviewer.’ ”

“I didn’t realize. I didn’t mean to insult you.”

“I don’t think many people remember our real title anymore,” Haggerty reassured her.

The girl wasn’t willing to let herself off the hook that easily. “I should have known. I’ve been researching the issue. I wouldn’t fight against something I hadn’t tried to understand first.”

She stopped. Haggerty studied her as she worried her lower lip, struggling with whatever it was she wanted to tell him. Her hair was sandy brown, her expressive green eyes set above high cheekbones in a classic oval face. Her light golden complexion and pleasantly rounded figure were striking changes from what was now fashionable. Even her height wasn’t quite up to par. But Haggerty found her more appealing than any of the women whose images flashed across viewscreens and e-covers everywhere. The thought startled him.

The girl finally began speaking again. “I know this is nervy of me, after what I did today, but would you be willing to talk to me for a few minutes?” she asked, anxiously tugging the straps of the backpack slung over her shoulder.

“I’m sorry,” he said. “I’m sort of in a hurry.”

“Please,” she whispered softly. “I have questions only someone like you can answer.”

Maybe it was the sincerity with which she asked, or that she was truly as young as she appeared. Or maybe it was that she looked as tired as Haggerty felt. Whatever the reason, he hesitated. BBI had strict rules. Confrontations with protesters were to be avoided, and a private conversation with one was guaranteed to lead to confrontation. But the girl seemed harmless, and anyway he wouldn’t be around long enough for disciplinary charges to be filed against him. He wasn’t sure he knew anymore why people pressed, or why someone would make a career of reviewing those presses. Maybe she had answers for him.

“Sure,” he said. “What’s your name?”

“Regina,” she said, visibly relieved.

He took her to the Java Joint, one of his favorite haunts, an unimposing little cafe not far from BBI headquarters to which he usually came alone. All white plasticine furniture, white tiled floors, and white painted walls, the Java Joint served the best coffee in NewVada — real coffee, made from real coffee beans. Haggerty often wondered where they got the beans from, but had never asked. During his parents’ day, beans were imported from places like Costa Rica, Peru, or as far away as Indonesia, but that was before the sanctions had been put in place.

He lifted his cup, savoring the dark, bitter brew. “Tell me why you’re protesting against BBI, Regina,” he said. “Why do you think we’re doing something wrong?”

Her green eyes narrowed. Now that she had him alone, she didn’t seem to know what to do with him.

“Tell me honestly,” he coaxed her. “I mean, besides the pro-life bit.”

“You mean the Sixth Commandment,” she said with a grin, taking the sting out of the words. “ ‘Thou shalt not kill’?” She sipped her coffee, leaving a purple lipstick smudge on the rim of her cup, either not noticing or unimpressed by its quality. “I know that you wouldn’t do what you do if you didn’t believe it was right. But I believe that suicide is self-murder. It used to be a crime.”

“It still is, if you use any method other than the Kevorkian unit.” The image of his father’s body flashed painfully across Haggerty’s mind.

“I know that you’re not fitted for a button unless you’ve already passed a psycheval that proves you can make a rational decision about ending your own life,” she said. “But that just gives you a free pass to do away with yourself at any time, without really thinking it through. When they first made suicide legal, you had to give notice of intent and wait a few days, giving you a chance to reconsider. It’s not like that anymore.”

“That was a very different time. There were so many other ways you could die, and it was certain that you would die decades, maybe even a century or two, before natural causes will kill you today. Our lives are so long now, it’s inevitable that sometimes people have had enough of living. But you’re young; I can understand that it’s hard for you to accept that.”

She shook her head. “I’m always being told that I’m too young to understand things, too young to make an informed choice, too young to think for myself,” she said quietly.

“I don’t believe you’re too young to think for yourself, just too young to have the experience to see all the aspects of a given situation.”

“There are other sources of wisdom, other ways to learn than experience,” she said. She leaned forward, her eyes passionate. “Ever read the Bible?”

“Decades ago,” Haggerty said. “I prefer the Buddhist approach. Suicide is viewed as a negative act, because it ends life, but in extreme situations it’s acceptable, if it ends one’s suffering or the suffering of others, which only you can judge.”

“I’m not talking about judgment or religious philosophy, I’m talking about overlooked science.”

Haggerty arched a brow.

“Got a pen?” Regina asked.

Haggerty pulled one from a pocket and handed it to her. She undid her napkin and sketched a graph, on which she drew a line.

“This is Adam, Old Testament times. Genesis 5:5. The Bible says he lived to be nine-hundred-thirty years old.”

She drew another line.

“Over a thousand years later, Lamech lived to be seven-hundred-seventy-seven.”

“He would’ve wanted a button, I’m sure,” Haggerty joked.

Regina smiled. “Maybe I can shake up that certainty.”

He smiled back. “You’re welcome to try.”

“Methuselah lived to be nine-hundred-sixty-nine. The Bible doesn’t present these numbers as miraculous or extraordinary. They’re just stated. It was commonplace to live that long.”

“I don’t think those numbers are meant to be taken literally,” Haggerty said.

Regina nodded emphatically. “As many intellectuals and bagbiters have argued. They suggest that back then each month may have been misinterpreted as a year. Divide by twelve, that’d make Methuselah about eighty-one. That fits nicely, right?”

“Yes,” Haggerty said.

“Except that they also recorded that Cainan was seventy when his first son was born. Divide that by twelve and Cainan was about five years old when he became a father. Think that’s probable?”

“The Bible was compiled by different writers,” Haggerty countered. “Obviously, some used the twelve-month rule and some didn’t.”

“Convenient theory,” Regina said airily. “But wrong.” She drew a new line. “Noah lived to be nine-hundred-fifty. Then came the Flood. Noah built the Ark and God did some global sterilization. And before you say the Flood’s not accepted fact, ask an archeologist about the layers of clay deposits in what used to be Mesopotamia, or the universality of contemporaneous flood layers around the world.”

Haggerty raised his hands in playful acquiescence.

“This is where things drop off considerably,” she continued. “By two-thousand B.C., Abraham only lived to be one-hundred-seventy-five, Joseph one-ten.”

Haggerty finally caught her meaning. “You’re saying the Flood changed something major in our ecosystem.”

“It introduced things that were harmful to us by design,” Regina said. “Radiation. Bacteria. Viruses. Things that decreased what was once our natural lifespan. David only made it to seventy-one, Solomon to fifty-eight.”

Haggerty hadn’t heard this analysis before, and doubted Regina had come up with it on her own. She seemed like an enthusiastic student reciting her latest lessons. He’d bet she was regurgitating some more complex oration, but couldn’t imagine whose.

“Solomon’s lifespan was pretty near the mark for most of recorded history,” he pointed out. “It wasn’t until the medical advances of the twentieth century that people began to live longer lives, and of course stem cell and telemor research resulted in our current longevity. How does the Biblical trend toward diminished lifespans fit in now?”

“Don’t you see,” Regina said earnestly, “all medical science has done is give us back what we had before. We’re supposed to live hundreds of years. Black buttons are just a quick cure for sadness or loneliness, cures that wouldn’t be needed if people gave themselves time to work through issues.”

Haggerty sipped his coffee, recalling post-press reviews on pushers who’d changed their minds. Abandoned attempts rarely exceeded fifteen minutes of tape, those mysterious “dark zones” where they’d planned to press and succumbed to survival instinct — or maybe an incoming call.

“Before black buttons, suicide wasn’t only illegal, it was tough to do, right?” Regina continued. “You had to plan it, find a weapon, pick a building to jump off. It was going to be painful and even messy. BBI took all that away. Someone having a bad day or just a bad moment can make a bad decision and — ” She snapped her fingers like a challenge. “By making death so accessible and painless, your company’s hijacked the natural barriers most people need to really consider the choice to die. It gives them an instant, selfish escape from responsibility.”

“Responsibility to whom?” he asked.

“To God,” she said. “Would He have allowed us to find a way to lengthen our lives again if He didn’t want us to live those lives fully? And each other. Do people who press stop to think how their friends and families will feel about their deaths? Their children, their partners, their parents? Maybe you don’t believe you owe God or your family a thing. But if you’re really a Buddhist, don’t you have a responsibility to yourself to learn as many lessons as you can in this lifetime?

“I say, live and love as long as you can. Make the best of whatever life hands you. Tired of your body? Save to get it retrofit. Bored with your job? Change careers or go back to school and learn something new. Get a hobby. Take a trip. Make new friends. Visit old friends. Whatever. Pressing’s not the answer.”

“Then what is?” Haggerty said flatly. He was damned sure that the pain that had driven him to decide to press couldn’t be assuaged by a world cruise, a year’s worth of tango lessons, or all the plastiche money could buy. People who pressed had done what Regina said they should do. They’d lived as long as possible and when they couldn’t continue, they had taken the legal, responsible, government-approved way to end their lives. Things seemed so clear to the young; the world was black and white. Haggerty knew that age brought a myriad of gray complexity, of living life and dying from it.

“There’s another way to look at this,” he said, thinking back to his conversation with Doug. “If God sent the Flood, then He intended the lifespan He initially gave us to be reduced. Maybe it’s the way we’ve gone about lengthening our lives that’s the problem, and the Kevorkian unit is really an instrument of Divine Will.”

“That’s close to blasphemy,” Regina said dryly. “The Catholic Church still holds that suicide brings eternal damnation.”

“You don’t truly believe that if you press you’ll end up in hell, do you?” Haggerty asked, unable to keep from smiling.

Regina looked away. Sensing he’d somehow touched a sore spot, Haggerty changed topics.

“Are you still in school, Regina?”

“I was,” she said, absentmindedly. “But I dropped out when my mom . . .”

There it was, the person she’d lost before she was prepared to let her go, the reason she was so opposed to KV units. Her mother must have pressed recently, and he’d just belittled her memory, smiled at what might be a tremendous, unresolved fear for her daughter.

“I’m sorry,” he said. “This must be a difficult time for you. But I can’t believe that, if there is a God, He’d sentence us to eternal hellfire for ending our own suffering. Is your father still around?”

“Never was,” she said. “I was an accident. Quality byproduct of a one-night-stand.”

Haggerty was surprised. Compulsory contraception at puberty insured that there were no accidents, no unplanned pregnancies. Unless . . .

“It didn’t happen here in the States,” she said, answering the unspoken question. “We emigrated when I was a kid.” Regina stared at the floor.

What was logic in the face of grief? Haggerty mused. Abandonment must have driven her to seek solace in religious doctrine.

“Why did you quit school, Regina?”

“I saw how useless it was,” she said. “You can’t be hired full-time before you’re thirty, and most people don’t get a real job until they’re fifty or older. Then, if you’re lucky, you get a job that you hate. Any post worth having is already filled by some oldster who’s been holding on to it for at least half a century.”

Haggerty inwardly winced, although she did not seem to be accusing him. Had his body reflected his true age, she probably would not be with him now.

“Unfortunately, the way your system works, only when someone presses does someone else get a good job.”

“Fair enough,” Haggerty admitted. “I can understand why a college degree seems like a waste of time, right now. But didn’t you just suggest we have a responsibility to ourselves to learn as many lessons as we can in this lifetime? To keep us from giving up and pressing? Trust me, you’re going to eventually realize that you need the competitive edge a degree gets you. My advice is to go back to school, when you’re ready of course. What were you studying by the way?”

“Programming, like all the other drones. My entire generation is gonna be nothing more than code monkeys and data farmers for yours. Unless you’re an athlete, or some trillionaire’s brat, ya know? I’m neither, so I’m learning all right. I’m learning to crack.” She grinned at him. “You’d arrest me if you saw some of the things I’ve already done.”

“I’m not a police officer,” he said mildly. “I’m just the button collector, remember?”

“You don’t see the people who use the buttons you collect, do you?”

Haggerty was confused by her question. “You mean, after they’re . . . ?”

She shook her head no. “I mean, you don’t meet them when they sign up?”

“I’m not a sales rep or a fitter,” he said. “I guess you might say I sort of meet them after they press.”

“You see their final moments, on recordings. How long are they?”

“Sometimes a few seconds, sometimes they go on for hours. The units have several shivabytes of memory. They warn you if you exceed capacity, then disarm.”

“Do you save them forever? Are they uploaded? Could I . . .”

“Crack into our system and retrieve one?”

Haggerty supposed she thought seeing a recording might help her understand why people pressed. But most likely she would see someone at the last reaches of despair, and he wasn’t sure she’d see why the press seemed to be the best answer. It didn’t matter. However good a cracker she was, the BBI safeguards were better.

“I doubt you’d be able to pull it off,” he told her. “And you’d be guilty of a felony for trying.”

“I’m not saying I would.”

“I’m not saying you did.”

Her lips curved upward. “I bet I could,” she said mischievously.

Haggerty laughed.

Excerpt from The Killswitch Review, published by Yard Dog Press. Copyright 2011 Steven-Elliot Altman.

Steven-Elliot Altman is a bestselling author, screenwriter, and videogame developer. He won multiple awards for his online role playing game, 9Dragons. His novels include Captain America is Dead, Zen in the Art of Slaying Vampires, Batman: Fear Itself, Batman: Infinite Mirror, The Killswitch Review, The Irregulars, and Deprivers. His writing has been compared to that of Stephen King, Dean Koontz, Michael Crichton and Philip K. Dick, and he has collaborated with world class writers such as Neil Gaiman, Michael Reaves, Harry Turtledove and Dr. Janet Asimov. He’s also the editor of the critically acclaimed anthology The Touch, and a contributor to Shadows Over Baker Street, a Hugo Award winning anthology of Sherlock Holmes meets H.P. Lovecraft stories.

Steven also bares ink on his body, and is bi, as in bi-coastal, between NYC and LA. He’s currently hard at work writing and directing his latest videogame Cursed Love, an online free to play gothic horror RPG from Dark Hermit Studios, set in Victorian London. Think Sherlock Holmes, Jack The Ripper and Dorian Gray mercilessly exploit the cast of Twilight. Friend Cursed Love (Official Closed Beta) on facebook and you can have fun playing out this tawdry, tragic romance with Steven while the game is being beta tested!

Diane DeKelb-Rittehouse spent several years in Manhattan as an actress before marrying her college sweetheart and returning to the Philadelphia area where she had been born. Diane first worked with Steven-Elliot Altman when they created the acclaimed, Publisher’s Weekly Starred-Review anthology The Touch: Epidemic of the Millennium, in which her story “Gifted” appeared. Diane has published a number of critically acclaimed short stories, most notably in the science fiction, murder, and horror genres. Her young adult fantasy novel, Fareie Rings: The Book of Forests, is now available in stores or online.

Interested in buying a printed copy of The Killswitch Review? Well, Steve’s publisher Yard Dog Press was kind enough to put up a special page where SuicideGirls can get a special discount and watch a sexy trailer. Just follow this link to KillswitchReview.com and click on the SG logo.

Fiction Friday: The Killswitch Review – Chapter One

Fiction Friday: The Killswitch Review – Chapter One, Part Two

Fiction Friday: The Killswitch Review – Chapter One, Part Three

Fiction Friday: The Killswitch Review – Chapter One, Part Four